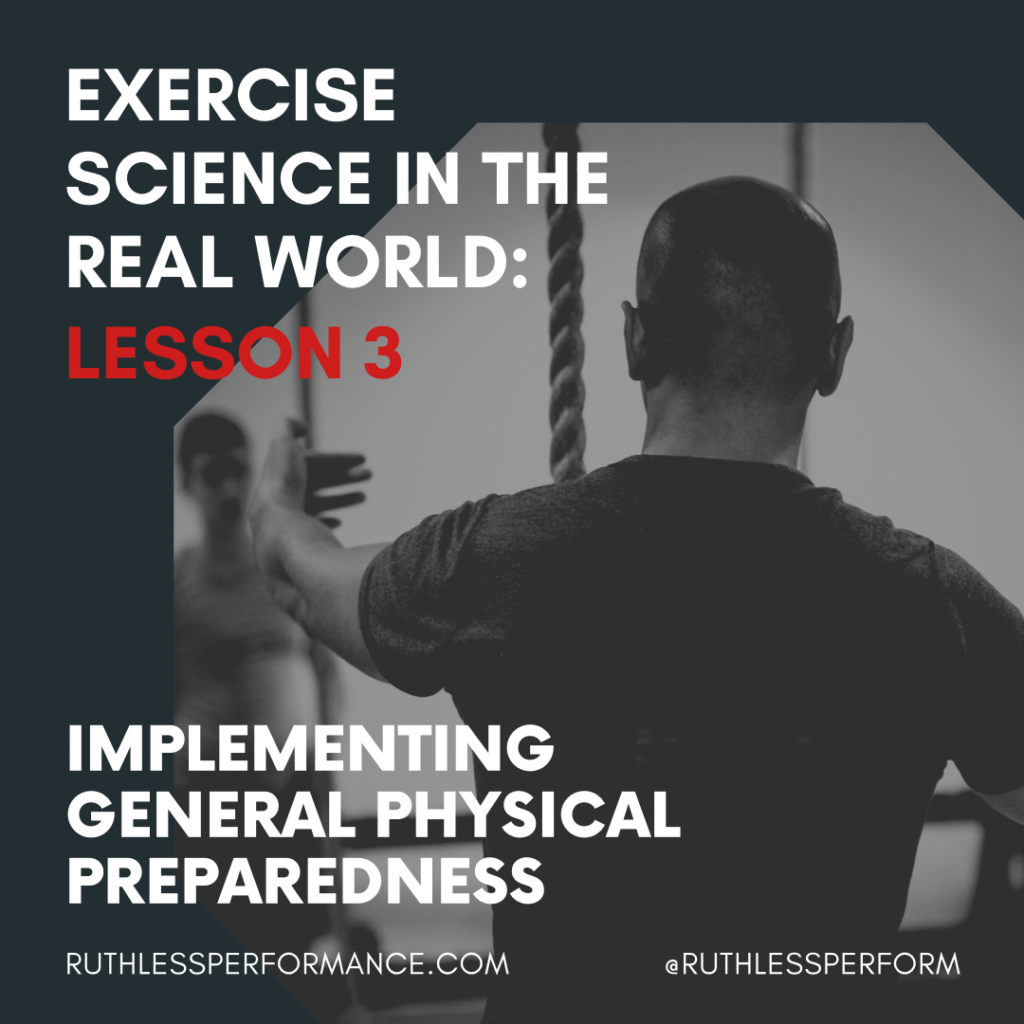

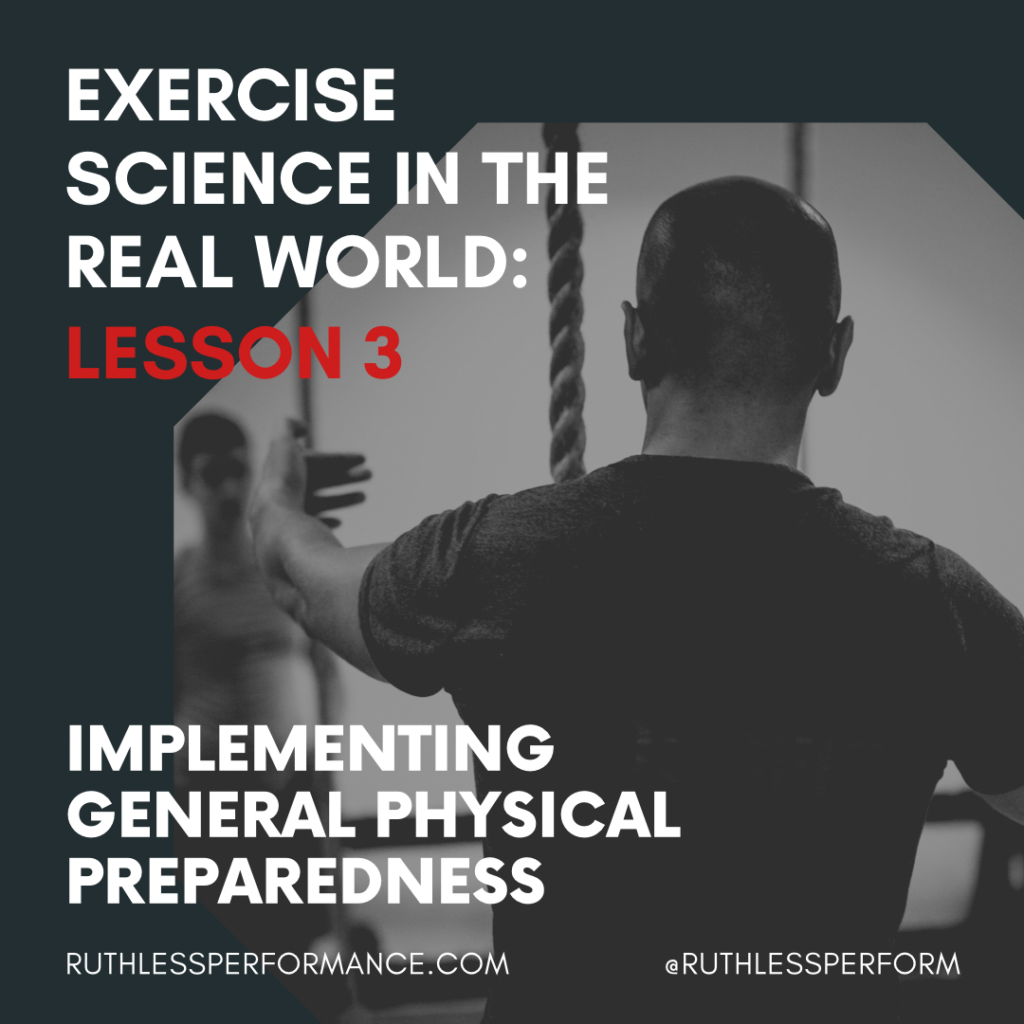

**Editor’s Note: This series comes from current Ruthless Performance Intern and Assistant Strength & Conditioning Coach, Keith Lowery. Keith is a senior exercise science student at Bloomsburg University, which has an affiliate agreement with Ruthless. As senior exercise science students complete their 4-year program, they are required to complete an arduous semester-long internship. These lessons will be presented weekly as interns gain real-world experience in the realm of strength and conditioning during crucial on-the-job education.**

GPP for your Athletes

In my last post I wrote about the importance of general physical preparedness (GPP) and how all athletes need a general exercise base to perform to the best of their ability. In this post I will be discussing the importance of GPP for your selected athletes.

Programming will change from athlete to athlete due to the needs of their sport and their individual weak points. Finding these weak points must be done within the first few weeks of training an athlete. The best way to do this is by giving them simplified versions of the main three strength exercises, the squat, bench, and deadlift and seeing how they perform them. I observed this first hand last week when the mad scientist himself, John, started training a new athlete.

One exercise John used when training this athlete was a partial range of motion kettlebell deadlift. Instead of picking the weight up off the floor he set up three forty five pound plates as a starting point so the athlete did not have to bend as far to grab the weight. He then had the athlete complete a few repetitions to see how they completed it and what muscles they relied on the most.

Taking the time to observe all of the repetitions from top to bottom can highlight where the athlete is weakest and which areas must be hit the most. So then programming can change accordingly. An athlete that has strong quadricep muscles will not get the same benefit from a front squat as an athlete that does not have the same strength, and changes must be made accordingly.

As a general observation, most athletes lack adequate posterior chain strength, meaning the back, glutes, and hamstrings to even maintain proper posture when standing normally. A good starting point for any athlete is to test them for their overall posterior chain strength, which John did using that partial range of motion kettlebell deadlift.

To correct this lack of posterior chain strength, the movements must be broken down to easier single joint exercises to pinpoint the weaknesses. For example, for glute strength, banded pull throughs or weighted hip thrusts are a must as they also show your athlete how to properly activate their glutes since they really never learned from never using them and sitting all day with the gluteal muscles in a relaxed position.

For sports that do not require much aerobic endurance conditioning, their training should not consist of long distance running, biking, or swimming because it can hinder the athletes anaerobic endurance for shorter ranges. When it comes to conditioning, focus more on what the sport requires. For endurance athletes, they will benefit from strength training, this is why GPP is so important, the stronger they are the more efficient and less work they must do to compete a race.

For endurance athletes, they will benefit from strength training, this is why GPP is so important, the stronger they are the more efficient and less work they must do to compete a race. Click To TweetAs stated above a general strength and conditioning base is the foundation for athletics. Strength coaches should make a starting program that has proven exercises as “testers” to see where athletes are strength wise and where their weaknesses lay.

Because the athlete can only be strong as their weakest links.